I was unusually proud of Obama today when I saw that he was making a full-throated defense of free expression in the wake of today’s savage attack of the offices of Charlie Hebdo in Paris. It’s good to see Obama standing up for human rights, and more importantly for the core values of our civilization: the values that have lead to unparalleled freedom and prosperity for billions of people globally. It is sad to see these values under threat today, in today’s attack and others, by those who think that being offended is a justification for murder.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen this particular brand of Islamist violence around the world in the last couple of years in response to “offense to Muslims.” A YouTube video allegedly provoked the protesters at Benghazi. Deadly riots ensued in Afghanistan and elsewhere after Terry Jones declared his intention to burn Qurans in Florida. Of course, we all remember when Danish embassies around the world were violently attacked, and riots broke out over the Muslim world where almost 200 people were killed, because Danish newspapers published cartoons depicting the prophet Muhammed.

It is one thing when this violence occurs abroad–in mob protests encouraged and sanctioned by corrupt regimes to score political points–it is quite another thing when violence hits the source. Therein do we we see the true contrast between the values of those who, despite what the apologists may think, wish to create a theocratic dictatorship, and those who seek to uphold civilized values of freedom of religion, expression and thought for all people. When Salman Rushdie was forced into exile by a fatwa issued on him and the assassination attempts that followed, the apologists on the left and the right condemned his alleged offense of Muslims instead of the hit put on him by a foreign preacher and the people who attempted to carry it out. We have seen Lars Vilks, Theo van Gogh, and others been murdered for offending Muslims, or in the case of Hitoshi Igarashi, murdered for translating a work alleged to have offended Muslims. We have seen attempted assassinations and death threats against Kurt Westergaard, Ettore Capriolo, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and others.

And now, we can add to the list of victims of Islamist violence the 12 cartoonists and journalists who were murdered in cold blood today by home-grown crazies shouting Islamic phrases in unaccented French as they proved, quite sadly, that the sword can be mightier than the pen. What happened in Paris is sickening and inexcusable, and it is good to see a near-universal condemnation of this violence as well as a full-throated defense of free speech.

But rest assured, the apologists have already started to come out of the woodwork. Ezra Klein–before the bodies were cold–wrote:

Their crime isn’t explained by cartoons or religion. Plenty of people read Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons and managed to avoid responding with mass murder. Plenty of people follow all sorts of religions and somehow get through the day without racking up a body count. The answers to what happened today won’t be found in Charlie Hebdo’s pages. They can only be found in the murderers’ sick minds.

It’s as if these people thought, “we should murder a bunch of journalists in cold blood,” and only then decided to research some religions, luckily finding one that offered the precise pretext they needed to accomplish their goals, and went about creating an elaborate backstory whereby their murders would now be justified because the victims had insulted their new ideology.

Klein goes on to say “can only be explained by the madness of the perpetrators, who did something horrible and evil that almost no human beings anywhere ever do.”

Except people do do it. They do it when they are instructed to by their religion. And it isn’t even a difficult leap to make: they said they did it to avenge their prophet. Why is that such a difficult pill to swallow?

Over the next couple of days, we expect to hear a predictable response from Klein and others like him: most Muslims are peaceful, Islam is not a religion of violence, this is all about politics, not religion, etc. And for the most part, these points are a distraction. Because of course most Muslims are peaceful. Of course most people–of any religion–only want to live their lives peacefully and prosperously.

But it’s a straw man. The question is “do we have a problem with the way Islam is understood and practiced by an unacceptably large number of people?” The answer is clearly yes. Are there crazy Christians and Jews and Hindus? Absolutely. But that, too, is a distraction. Islam is unique in the world today as a religion with a large number of followers who believe in values contrary to modern conceptions of human rights. Over 90% of Muslims in Iraq, Morocco, Tunisia, Indonesia, Afghanistan and Malaysia believe that a wife is always obliged to obey her husband, according to Pew. The same poll found that over 70% of Muslims in Egypt, Jordan, Afghanistan and Pakistan support the death penalty for apostasy.

Although most Muslims in the US are far more tolerant, 8% of American Muslims believe that suicide bombings are “sometimes” or “often” justified to defend Islam. That’s a scarily high percentage. It only takes one person to do something deadly.

This may sound like fear mongering, but it isn’t–I could put all the usual disclaimers in here: most Muslims are peaceful, I have Muslim friends, etc, etc. The fact is, that this has little to nothing to do with Muslims as people. It has to do with whether the civilized world–and that includes most Muslims–are doing enough to combat backwards thinking and medieval values. Are we truly doing what needs to be done to stand up for tolerance that allows people to practice their religion freely, but not intolerance that allows them to impose their religious beliefs on others through violence and intimidation?

The US probably has the best constitutional framework for this, in that, as a strictly secular political sphere with religious practice guaranteed freedom by the first amendment, we are able to strike a balance between the political and the personal. We should not follow the prescriptions of lunatics who think that banning Muslims from entering the country or outlawing religion is the solution. We should, however, be OK with enforcing our secularism to the benefit of Muslims, worldwide, who share the same values. These are the people who are most in danger–those who are actually tolerant and free-thinking, who are living under regimes or in societies that put them at risk for their beliefs. We need to stand up for the victims of Islamofascism, who are usually Muslims themselves, and protect them–let them emigrate, defend their rights abroad, call out their oppressors and support their revolutions.

The apologists will not get us there. The xenophobes won’t get us there. We need a third way.

Here’s where it starts: it starts by insisting that the values of the first amendment are not just American values, but global values. That people should be allowed to practice their religion freely as well as believe what they want to about anything, and that includes other religions or not having a religion at all. Most of all, people must be free to offend people who don’t agree with their ideas, because that’s the point of free expression. The first amendment doesn’t exist to give people the freedom to state a popular opinion. As Rosa Luxemburg said, “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.” Or, to put a finer point on it, from Rushdie himself: “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

Then, these values must be disseminated somehow, maybe through a combination of political and cultural ambassadorship.

At this point, though, I have to admit that I don’t know what’s actionable here. What can we actually do? Other than be on the right side of the debate, and standing up for values of modern civilization, how can we actually turn back the tide of an ideology that, if anything, is getting stronger and its followers more numerous? We can’t go to war against every nation whose values we don’t share. We can’t round up all Muslims because of a few bad apples. We are at risk of being impotent while we get bombed and shot at by an enemy that is far more motivated and bloodthirsty than we are.

So I don’t have the answers–I just think it’s important that we realize this is a problem, and that true liberals get on the right side of history to help come up with a solution.

The main theme of Les Miz, for the uninitiated, is redemption, but the story also focuses on the June 1832 Paris uprising, which was a failed one-night rebellion by students against the restored monarchy of Louis-Philippe, a rebellion to which Victor Hugo was clearly sympathetic in his original treatment. The musical has a rousing anthem for the rebellion, “Do You Hear the People Sing,” which makes up the finale, and consequently is being hummed by every audience member leaving the theater. In this anthem, we see the poor and downtrodden people of Paris fomenting revolution, joining forces against the powerful and entrenched elites as they suffer in the street. It is a powerful moment in the film which has the audience on its feet cheering on the people against their oppressors, yet it ends in tragedy as the young students all end up killed at their barricades as the people they hoped to join their movement shutter their windows. The cause of the rebels and what they died for is all but forgotten to history, and would be only a footnote if Victor Hugo hadn’t enshrined it in his book. And we are left thinking about the almost pathetic nature of the failed rebellion; that final moment when the students realized that their brief moment of agitation has resulted in only their own demise.

The main theme of Les Miz, for the uninitiated, is redemption, but the story also focuses on the June 1832 Paris uprising, which was a failed one-night rebellion by students against the restored monarchy of Louis-Philippe, a rebellion to which Victor Hugo was clearly sympathetic in his original treatment. The musical has a rousing anthem for the rebellion, “Do You Hear the People Sing,” which makes up the finale, and consequently is being hummed by every audience member leaving the theater. In this anthem, we see the poor and downtrodden people of Paris fomenting revolution, joining forces against the powerful and entrenched elites as they suffer in the street. It is a powerful moment in the film which has the audience on its feet cheering on the people against their oppressors, yet it ends in tragedy as the young students all end up killed at their barricades as the people they hoped to join their movement shutter their windows. The cause of the rebels and what they died for is all but forgotten to history, and would be only a footnote if Victor Hugo hadn’t enshrined it in his book. And we are left thinking about the almost pathetic nature of the failed rebellion; that final moment when the students realized that their brief moment of agitation has resulted in only their own demise. But the overwhelming weight of history seems to be against violent revolution as a solution to political problems, even when it is successful. In the cases where revolutions have been successful, they have either been regime changes where there was enough popular pressure to dismantle the status quo without much violence, or they have been violent overthrows resulting in a drastically reduced quality of life for the greater society, and often a society very much different than the one intended by the revolutionaries.

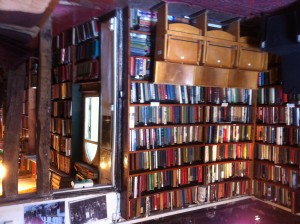

But the overwhelming weight of history seems to be against violent revolution as a solution to political problems, even when it is successful. In the cases where revolutions have been successful, they have either been regime changes where there was enough popular pressure to dismantle the status quo without much violence, or they have been violent overthrows resulting in a drastically reduced quality of life for the greater society, and often a society very much different than the one intended by the revolutionaries. Friday my host, Jonathan, went to work so I went to the left bank, to Shakespeare and Company. It is not the same Shakespeare and Company Hemingway fondly remembered in A Moveable Feast, but it is at least half a century old and filled with books and tourists to read the books. The reading room upstairs was nearly empty when I went upstairs and finished A Moveable Feast looking out on Notre Dame across the river. It became the fifth Hemingway I have read, making Hemingway one of my most frequented authors. I picked up a copy of Green Hills of Africa while there, and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by Joyce. It seemed appropriate to purchase the books at their authors’ inspirational nexus. Friday night I met up with Jonathan and he took me to shabbat dinner with his cousin and his girlfriend and two other friends. Aside from the opening kiddush, the dinner was like any other and flowed with wine and rapid conversation. Malheureusement my French competency is not what it might be and I found it very difficult to participate at speed with my hosts, who were gracious enough to include me in English several times in the conversation. I found that it was much easier for me to understand the flow of conversation than to speak, and although many things slipped past me–notably all the joke punchlines–I was able to understand the humor of dialogue and participate as such. Jonathan and I had discussed my libertarianism earlier that day, and he brought it up at the dinner table which led to a short interchange about the relative merits of American-style individualism and French-style communitarianism. Jonathan and his friends are in the upper strata, more or less, of French society, so it was interesting to hear their take on French society and what they expected from the future. Jonathan’s cousin and his girlfriend are moving to Singapore, and Jonathan will be trying to move to the US as soon as possible. Critics of American exceptionalism will often point out how much better various indicators are in other countries in the world, especially Europe, but I found it revealing how desperately these young people in this particular class are trying to flee France, a country that, after all, has been very good to them and their families. I heard many times how America was the greatest country in the world. I also found it interesting one passionate defense of French socialism by a guest at the table, in light of the fact that most of the people she knows are trying to flee French socialism as soon as possible–and the new 75% tax imposed by François Hollande doesn’t help the situation. At one point the subject of pig latin came up and I became the de facto educator of pig latin at the table. My French friends had never heard of pig latin before, and were quite amused in their attempts to speak it despite their many errors. Michael, our host, had particular trouble translating the “ay” sound, instead using “ah,” much to the amusement of his girlfriend. One thing I noticed, being a passive observer of dinner conversation without the ability to participate, was the flow of conversation topics. As the proverbial fly on the wall I was able to follow the conversation from elephants to caves to attics to rumors to politics to airplanes to consulting to business to chocolate and that was 4 hours. I found the simultaneous attempt to follow the conversation and understand French and drink wine to be quite exhausting, but worth the experience. It has only motivated me more to learn French much much better, a promise I made to Jonathan and I intend to keep. Friday night we crashed and slept in the next day.

Friday my host, Jonathan, went to work so I went to the left bank, to Shakespeare and Company. It is not the same Shakespeare and Company Hemingway fondly remembered in A Moveable Feast, but it is at least half a century old and filled with books and tourists to read the books. The reading room upstairs was nearly empty when I went upstairs and finished A Moveable Feast looking out on Notre Dame across the river. It became the fifth Hemingway I have read, making Hemingway one of my most frequented authors. I picked up a copy of Green Hills of Africa while there, and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by Joyce. It seemed appropriate to purchase the books at their authors’ inspirational nexus. Friday night I met up with Jonathan and he took me to shabbat dinner with his cousin and his girlfriend and two other friends. Aside from the opening kiddush, the dinner was like any other and flowed with wine and rapid conversation. Malheureusement my French competency is not what it might be and I found it very difficult to participate at speed with my hosts, who were gracious enough to include me in English several times in the conversation. I found that it was much easier for me to understand the flow of conversation than to speak, and although many things slipped past me–notably all the joke punchlines–I was able to understand the humor of dialogue and participate as such. Jonathan and I had discussed my libertarianism earlier that day, and he brought it up at the dinner table which led to a short interchange about the relative merits of American-style individualism and French-style communitarianism. Jonathan and his friends are in the upper strata, more or less, of French society, so it was interesting to hear their take on French society and what they expected from the future. Jonathan’s cousin and his girlfriend are moving to Singapore, and Jonathan will be trying to move to the US as soon as possible. Critics of American exceptionalism will often point out how much better various indicators are in other countries in the world, especially Europe, but I found it revealing how desperately these young people in this particular class are trying to flee France, a country that, after all, has been very good to them and their families. I heard many times how America was the greatest country in the world. I also found it interesting one passionate defense of French socialism by a guest at the table, in light of the fact that most of the people she knows are trying to flee French socialism as soon as possible–and the new 75% tax imposed by François Hollande doesn’t help the situation. At one point the subject of pig latin came up and I became the de facto educator of pig latin at the table. My French friends had never heard of pig latin before, and were quite amused in their attempts to speak it despite their many errors. Michael, our host, had particular trouble translating the “ay” sound, instead using “ah,” much to the amusement of his girlfriend. One thing I noticed, being a passive observer of dinner conversation without the ability to participate, was the flow of conversation topics. As the proverbial fly on the wall I was able to follow the conversation from elephants to caves to attics to rumors to politics to airplanes to consulting to business to chocolate and that was 4 hours. I found the simultaneous attempt to follow the conversation and understand French and drink wine to be quite exhausting, but worth the experience. It has only motivated me more to learn French much much better, a promise I made to Jonathan and I intend to keep. Friday night we crashed and slept in the next day. Saturday Jonathan and I met up with Michael for petit déjeuner where we had croissants and hot chocolate and toast with honey and orange juice. Michael unfortunately is recovering from a fractured shin, so he is on crutches and our walking range was limited. We drove into the city and parked on Île de la Cité. As we got out of the car, someone across the Seine decided to dive in for an afternoon swim. He paddled around in the river for a couple minutes before a patrol boat fished him out. We crossed the bridge and descended upon Paris Plage, a new initiative whereby a “beach” has been built on the formerly paved bank of the Seine. This beach is one lane of traffic wide and is basically a sand pit. Many children play with sand pails and parents bring beach chairs, but this is not a beach. I learn that Paris Plage was met with derision as a project, both for its cost and its disruption of summer traffic, which we got a taste of on our drive down the right bank. It seems pretty silly in retrospect, but I suppose enough people are enjoying themselves on this “beach” to make it worthwhile. The bank of the Seine also hosted a disappointingly awful dance trio who inexplicably drew a huge crowd. After our brief excursion to the beach, we went back to the seizième and got sushi takeout for a picnic. We picked up Michael’s and Jonathan’s girlfriends and all ended up at the park with our sushi and fruit picnic. More French was spoken. More English was spoken with me than before. Wine was flowing. After the picnic we went to the cinema on Champs-Élysées and saw Starbuck, a Quebecois movie about a sperm donor who, 20 years later, finds out he has 500 children that want to meet him. It was an endearing movie but not that good. It was in Quebecois French without subtitles. I understood most of it. After the movie we relaxed at home for a bit before going out for a party. The party was good. I learned that in France, many people learn English using textbooks starring a character named Brian. The question is posed to the students, “Where is Brian?” to which the students respond, “Brian is in the kitchen.” It thus became imperative to take a picture of Brian in the kitchen. We did. The party lasted until 5am. I had a train to catch at 9am. I crashed. The French stayed out for two more hours.

Saturday Jonathan and I met up with Michael for petit déjeuner where we had croissants and hot chocolate and toast with honey and orange juice. Michael unfortunately is recovering from a fractured shin, so he is on crutches and our walking range was limited. We drove into the city and parked on Île de la Cité. As we got out of the car, someone across the Seine decided to dive in for an afternoon swim. He paddled around in the river for a couple minutes before a patrol boat fished him out. We crossed the bridge and descended upon Paris Plage, a new initiative whereby a “beach” has been built on the formerly paved bank of the Seine. This beach is one lane of traffic wide and is basically a sand pit. Many children play with sand pails and parents bring beach chairs, but this is not a beach. I learn that Paris Plage was met with derision as a project, both for its cost and its disruption of summer traffic, which we got a taste of on our drive down the right bank. It seems pretty silly in retrospect, but I suppose enough people are enjoying themselves on this “beach” to make it worthwhile. The bank of the Seine also hosted a disappointingly awful dance trio who inexplicably drew a huge crowd. After our brief excursion to the beach, we went back to the seizième and got sushi takeout for a picnic. We picked up Michael’s and Jonathan’s girlfriends and all ended up at the park with our sushi and fruit picnic. More French was spoken. More English was spoken with me than before. Wine was flowing. After the picnic we went to the cinema on Champs-Élysées and saw Starbuck, a Quebecois movie about a sperm donor who, 20 years later, finds out he has 500 children that want to meet him. It was an endearing movie but not that good. It was in Quebecois French without subtitles. I understood most of it. After the movie we relaxed at home for a bit before going out for a party. The party was good. I learned that in France, many people learn English using textbooks starring a character named Brian. The question is posed to the students, “Where is Brian?” to which the students respond, “Brian is in the kitchen.” It thus became imperative to take a picture of Brian in the kitchen. We did. The party lasted until 5am. I had a train to catch at 9am. I crashed. The French stayed out for two more hours. The next day I took the train to London at 9 in the morning. The Eurostar train was high speed and whipped through the chunnel at breakneck speed, leaving us with our ears popped on both ends. London is gearing up for the Olympics, but I saw none of it, opting to catch a train to Oxford to see my good friend for lunch, before turning around and coming back to Hampton Court Palace where my family rented the Fish Court to have a reunion, 16 years later, of our first family vacation. It’s a full week of vacation for them, but I was only there for the night. Dinner was at a new Lebanese restaurant in the town, and dessert was a bottle of Graham’s port bottled 1912–its 100 year anniversary. It is hard to imagine how much different the world was when every person who made that bottle was alive and well and optimistic. It has been only 100 years, a blink in history, but an eternity for a young mortal trying to imagine how dead and buried he will be when 2112 rolls around. In the last century there were two world wars, three brutal totalitarianisms, the transformative liberalization of the global economy, the internet and the politics of interconnectivity, a cold war and a space age. It is hard to imagine what will happen in the next 100 years. The port was delicious and perfectly preserved.

The next day I took the train to London at 9 in the morning. The Eurostar train was high speed and whipped through the chunnel at breakneck speed, leaving us with our ears popped on both ends. London is gearing up for the Olympics, but I saw none of it, opting to catch a train to Oxford to see my good friend for lunch, before turning around and coming back to Hampton Court Palace where my family rented the Fish Court to have a reunion, 16 years later, of our first family vacation. It’s a full week of vacation for them, but I was only there for the night. Dinner was at a new Lebanese restaurant in the town, and dessert was a bottle of Graham’s port bottled 1912–its 100 year anniversary. It is hard to imagine how much different the world was when every person who made that bottle was alive and well and optimistic. It has been only 100 years, a blink in history, but an eternity for a young mortal trying to imagine how dead and buried he will be when 2112 rolls around. In the last century there were two world wars, three brutal totalitarianisms, the transformative liberalization of the global economy, the internet and the politics of interconnectivity, a cold war and a space age. It is hard to imagine what will happen in the next 100 years. The port was delicious and perfectly preserved. The latest outrage is a new ban in France which

The latest outrage is a new ban in France which