I’ve had a complicated relationship with the 44th Commander in Chief.

For starters, I helped get him elected. I served on the New Media Team as a volunteer for his first presidential campaign in 2008. I got to work with some incredible people: Chris Hughes, Arun Chaudhary, Dan Siroker, Michael Slaby, Gray Brooks, and many more, all of whom went on to do extraordinary things.

I was in Denver for the 2008 convention where, though not able to score an invite to the floor, I was able to witness an America divided by the hot button issues of the day, some of which are still with us: same-sex marriage, abortion, the war in Iraq, and immigration. I watched the DNC convention speeches with anticipation and excitement for the next eight years, fully swept up in the anti-Bush furor and pro-Obama fervor of the time.

I was in Denver for the 2008 convention where, though not able to score an invite to the floor, I was able to witness an America divided by the hot button issues of the day, some of which are still with us: same-sex marriage, abortion, the war in Iraq, and immigration. I watched the DNC convention speeches with anticipation and excitement for the next eight years, fully swept up in the anti-Bush furor and pro-Obama fervor of the time.

Despite some misgivings, I was all in on Obama. I thought his vision was the right thing for the country at the time. I thought his story, and especially his race, were poignant symbols of the progress America had made. He didn’t need to play the ‘race card’ because his candidacy was the ultimate race card. He proved to America that leadership, eloquence, savvy and hard work transcend race and class. He was also the ultimate foil to eight years of George W. Bush: the president that America loved to hate. Bush was born rich and coasted to the presidency. Obama was born poor and worked his way into it. Bush was a clumsy orator. Obama’s words soared. Bush was the voice of the special interests and the past. Obama was the voice of the disenfranchised and the future.

When we pulled the lever for Obama we believed we were making the world a better place. For a brief moment in history, Obama made us believe that Hope and Change were achievable political values. When we gathered in Grant Park in Chicago on Election Day, the minute the California polls closed and CNN flashed its projection, the crowd was so swept up in the profundity of that history-shaking moment that time seemed to freeze. I hugged a stranger that night and we cried.

As Obama would say on his way out of office eight years later, reality has a way of asserting itself. There really was no post-racial America, no progressive wave, no hope, and no change. America hated Bush enough to elect the most liberal candidate in history, and America corrected itself two years later when the Republicans took back the House of Representatives. The post-Obama swing has arguably continued into the 2016 election, bringing us the biggest wildcard in American history.

Even so, for the first couple years, I had more or less a positive feeling about Obama’s policies, and politics, until 2011 or so when my economic and political thinking took a hard libertarian tack and I found myself alienated towards my former political idol and the Democratic Party I thought reflected progress. The economy didn’t magically get better; healthcare wasn’t magically solved. I went through a personal journey that paralleled, perhaps, that of many in my generation: disillusionment, alienation, resentment, political realignment. I was probably one of many who watched with excitement and anticipation in 2009 when Congress voted on ACA, hoping that it would pass, and three years later nearly lost my mind when the Supreme Court refused to rule it unconstitutional.

Obama was still the president, but for me, for years he represented the worst of American politics. In my view, he was the face of the arrogance of Washington DC. His rhetoric that I had once praised as transcendent became bitter and divisive. He condescended to the masses with placations and platitudes and they bought it hook, line and sinker. I pulled the lever for Gary Johnson in 2012 and never regretted it.

Then, strangely enough, in 2013, my relationship to Barack Obama changed again. Living in the liberal capital of San Francisco, despite our political differences I happily partnered up with Max Slavkin and Aaron Perry-Zucker of the Creative Action Network, whose first product was a folio of pro-Obama propaganda (or as we called it, art). As their first CTO, I spent the next year creating an ecommerce and art submission platform to sell a litany of poster campaigns geared towards progressive causes with impactful results, including See America which now has a great book selling in the national parks. In San Francisco, I found myself pulled back into the progressive network of creatives and intellectuals I had spent the previous two years trying to avoid. I came to see that, despite our disagreements on many issues, their hard work to make the world a better place was admirable, and many of them continue to be close friends.

All the while, Barack Obama was my president, and the distance between us started to shrink. Second term Obama was my flavor much more than first term Obama. I admired his work on criminal justice reform. I was extremely supportive of the Trans-Pacific Partnership and watched with dismay as that fell apart. His actions on Cuba and Iran were exciting. I even cheered Kerry’s recent foray into the thorny Israeli settlement issue. I celebrated when Obama ‘evolved’ on same-sex marriage, and celebrated more so in San Francisco the week the Supreme Court ruled it constitutional. Obama wasn’t perfect by any means, especially when it came to his expansion of drone strikes, surveillance power, executive privilege, his handling of Syria, and more. But over the last three years I have developed a newfound begrudging respect for the community organizer from Illinois.

Did Obama leave me, or did I leave Obama? And once separated, did he come back to me or did I come back to him? Did he become more centrist, more pragmatic in recent years? Or did we evolve towards each other, like a divided America dancing in disagreement towards a common truth? I know that my progressive friends feel somewhat betrayed by the Obama presidency, for the same reason that my conservative friends have felt warmer towards him in recent years. Maybe we all are changing in ways we wouldn’t like to admit. Or maybe Obama, the great pragmatist, has had his finger on the pulse of our generation in a way no one ever has.

Like all presidents, he leaves office with a mixed legacy. But for me, Obama was simply my president, for better or for worse. Like postwar Eisenhower, he is the president historians will feature when they turn the page into the 21st century. I think John McCain would have made a fine president, as would have Mitt Romney. But despite all my distrust of #44 and my concerns about his achievements, I have grown accustomed to That One and will be sad to see him go. Because, for better or for worse, America is turning the page again, and though we don’t know what the next chapter will bring, this one wasn’t all that bad.

In many ways, it is impossible for me to disentangle the history of Obama with my own history. It’s impossible not to think about the most powerful person in the world–someone who is always in your living room and on your computer screen–as part of your life. And like any other relationship, mine with Obama has had its ups and downs, and must now sadly come to an end. Not sadly because change, or even Trump, are inherently bad, sadly because Obama is the president I have gotten to know through the years and now he’s about to ride off into the sunset.

So, it is with only a tinge of irony that I close this obituary of my relationship with Barack Obama, happy to see the country still standing, hopeful for the next four years, and appreciative of the accomplishments of this undeniably impressive politician and man.

Thanks, Obama.

Something is definitely wrong when Pakistanis are rightfully protesting our government’s actions whilst we remain disturbingly silent.Never mind that the Justice Department

Something is definitely wrong when Pakistanis are rightfully protesting our government’s actions whilst we remain disturbingly silent.Never mind that the Justice Department  Friday my host, Jonathan, went to work so I went to the left bank, to Shakespeare and Company. It is not the same Shakespeare and Company Hemingway fondly remembered in A Moveable Feast, but it is at least half a century old and filled with books and tourists to read the books. The reading room upstairs was nearly empty when I went upstairs and finished A Moveable Feast looking out on Notre Dame across the river. It became the fifth Hemingway I have read, making Hemingway one of my most frequented authors. I picked up a copy of Green Hills of Africa while there, and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by Joyce. It seemed appropriate to purchase the books at their authors’ inspirational nexus. Friday night I met up with Jonathan and he took me to shabbat dinner with his cousin and his girlfriend and two other friends. Aside from the opening kiddush, the dinner was like any other and flowed with wine and rapid conversation. Malheureusement my French competency is not what it might be and I found it very difficult to participate at speed with my hosts, who were gracious enough to include me in English several times in the conversation. I found that it was much easier for me to understand the flow of conversation than to speak, and although many things slipped past me–notably all the joke punchlines–I was able to understand the humor of dialogue and participate as such. Jonathan and I had discussed my libertarianism earlier that day, and he brought it up at the dinner table which led to a short interchange about the relative merits of American-style individualism and French-style communitarianism. Jonathan and his friends are in the upper strata, more or less, of French society, so it was interesting to hear their take on French society and what they expected from the future. Jonathan’s cousin and his girlfriend are moving to Singapore, and Jonathan will be trying to move to the US as soon as possible. Critics of American exceptionalism will often point out how much better various indicators are in other countries in the world, especially Europe, but I found it revealing how desperately these young people in this particular class are trying to flee France, a country that, after all, has been very good to them and their families. I heard many times how America was the greatest country in the world. I also found it interesting one passionate defense of French socialism by a guest at the table, in light of the fact that most of the people she knows are trying to flee French socialism as soon as possible–and the new 75% tax imposed by François Hollande doesn’t help the situation. At one point the subject of pig latin came up and I became the de facto educator of pig latin at the table. My French friends had never heard of pig latin before, and were quite amused in their attempts to speak it despite their many errors. Michael, our host, had particular trouble translating the “ay” sound, instead using “ah,” much to the amusement of his girlfriend. One thing I noticed, being a passive observer of dinner conversation without the ability to participate, was the flow of conversation topics. As the proverbial fly on the wall I was able to follow the conversation from elephants to caves to attics to rumors to politics to airplanes to consulting to business to chocolate and that was 4 hours. I found the simultaneous attempt to follow the conversation and understand French and drink wine to be quite exhausting, but worth the experience. It has only motivated me more to learn French much much better, a promise I made to Jonathan and I intend to keep. Friday night we crashed and slept in the next day.

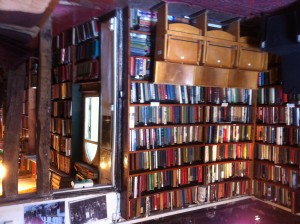

Friday my host, Jonathan, went to work so I went to the left bank, to Shakespeare and Company. It is not the same Shakespeare and Company Hemingway fondly remembered in A Moveable Feast, but it is at least half a century old and filled with books and tourists to read the books. The reading room upstairs was nearly empty when I went upstairs and finished A Moveable Feast looking out on Notre Dame across the river. It became the fifth Hemingway I have read, making Hemingway one of my most frequented authors. I picked up a copy of Green Hills of Africa while there, and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by Joyce. It seemed appropriate to purchase the books at their authors’ inspirational nexus. Friday night I met up with Jonathan and he took me to shabbat dinner with his cousin and his girlfriend and two other friends. Aside from the opening kiddush, the dinner was like any other and flowed with wine and rapid conversation. Malheureusement my French competency is not what it might be and I found it very difficult to participate at speed with my hosts, who were gracious enough to include me in English several times in the conversation. I found that it was much easier for me to understand the flow of conversation than to speak, and although many things slipped past me–notably all the joke punchlines–I was able to understand the humor of dialogue and participate as such. Jonathan and I had discussed my libertarianism earlier that day, and he brought it up at the dinner table which led to a short interchange about the relative merits of American-style individualism and French-style communitarianism. Jonathan and his friends are in the upper strata, more or less, of French society, so it was interesting to hear their take on French society and what they expected from the future. Jonathan’s cousin and his girlfriend are moving to Singapore, and Jonathan will be trying to move to the US as soon as possible. Critics of American exceptionalism will often point out how much better various indicators are in other countries in the world, especially Europe, but I found it revealing how desperately these young people in this particular class are trying to flee France, a country that, after all, has been very good to them and their families. I heard many times how America was the greatest country in the world. I also found it interesting one passionate defense of French socialism by a guest at the table, in light of the fact that most of the people she knows are trying to flee French socialism as soon as possible–and the new 75% tax imposed by François Hollande doesn’t help the situation. At one point the subject of pig latin came up and I became the de facto educator of pig latin at the table. My French friends had never heard of pig latin before, and were quite amused in their attempts to speak it despite their many errors. Michael, our host, had particular trouble translating the “ay” sound, instead using “ah,” much to the amusement of his girlfriend. One thing I noticed, being a passive observer of dinner conversation without the ability to participate, was the flow of conversation topics. As the proverbial fly on the wall I was able to follow the conversation from elephants to caves to attics to rumors to politics to airplanes to consulting to business to chocolate and that was 4 hours. I found the simultaneous attempt to follow the conversation and understand French and drink wine to be quite exhausting, but worth the experience. It has only motivated me more to learn French much much better, a promise I made to Jonathan and I intend to keep. Friday night we crashed and slept in the next day. Saturday Jonathan and I met up with Michael for petit déjeuner where we had croissants and hot chocolate and toast with honey and orange juice. Michael unfortunately is recovering from a fractured shin, so he is on crutches and our walking range was limited. We drove into the city and parked on Île de la Cité. As we got out of the car, someone across the Seine decided to dive in for an afternoon swim. He paddled around in the river for a couple minutes before a patrol boat fished him out. We crossed the bridge and descended upon Paris Plage, a new initiative whereby a “beach” has been built on the formerly paved bank of the Seine. This beach is one lane of traffic wide and is basically a sand pit. Many children play with sand pails and parents bring beach chairs, but this is not a beach. I learn that Paris Plage was met with derision as a project, both for its cost and its disruption of summer traffic, which we got a taste of on our drive down the right bank. It seems pretty silly in retrospect, but I suppose enough people are enjoying themselves on this “beach” to make it worthwhile. The bank of the Seine also hosted a disappointingly awful dance trio who inexplicably drew a huge crowd. After our brief excursion to the beach, we went back to the seizième and got sushi takeout for a picnic. We picked up Michael’s and Jonathan’s girlfriends and all ended up at the park with our sushi and fruit picnic. More French was spoken. More English was spoken with me than before. Wine was flowing. After the picnic we went to the cinema on Champs-Élysées and saw Starbuck, a Quebecois movie about a sperm donor who, 20 years later, finds out he has 500 children that want to meet him. It was an endearing movie but not that good. It was in Quebecois French without subtitles. I understood most of it. After the movie we relaxed at home for a bit before going out for a party. The party was good. I learned that in France, many people learn English using textbooks starring a character named Brian. The question is posed to the students, “Where is Brian?” to which the students respond, “Brian is in the kitchen.” It thus became imperative to take a picture of Brian in the kitchen. We did. The party lasted until 5am. I had a train to catch at 9am. I crashed. The French stayed out for two more hours.

Saturday Jonathan and I met up with Michael for petit déjeuner where we had croissants and hot chocolate and toast with honey and orange juice. Michael unfortunately is recovering from a fractured shin, so he is on crutches and our walking range was limited. We drove into the city and parked on Île de la Cité. As we got out of the car, someone across the Seine decided to dive in for an afternoon swim. He paddled around in the river for a couple minutes before a patrol boat fished him out. We crossed the bridge and descended upon Paris Plage, a new initiative whereby a “beach” has been built on the formerly paved bank of the Seine. This beach is one lane of traffic wide and is basically a sand pit. Many children play with sand pails and parents bring beach chairs, but this is not a beach. I learn that Paris Plage was met with derision as a project, both for its cost and its disruption of summer traffic, which we got a taste of on our drive down the right bank. It seems pretty silly in retrospect, but I suppose enough people are enjoying themselves on this “beach” to make it worthwhile. The bank of the Seine also hosted a disappointingly awful dance trio who inexplicably drew a huge crowd. After our brief excursion to the beach, we went back to the seizième and got sushi takeout for a picnic. We picked up Michael’s and Jonathan’s girlfriends and all ended up at the park with our sushi and fruit picnic. More French was spoken. More English was spoken with me than before. Wine was flowing. After the picnic we went to the cinema on Champs-Élysées and saw Starbuck, a Quebecois movie about a sperm donor who, 20 years later, finds out he has 500 children that want to meet him. It was an endearing movie but not that good. It was in Quebecois French without subtitles. I understood most of it. After the movie we relaxed at home for a bit before going out for a party. The party was good. I learned that in France, many people learn English using textbooks starring a character named Brian. The question is posed to the students, “Where is Brian?” to which the students respond, “Brian is in the kitchen.” It thus became imperative to take a picture of Brian in the kitchen. We did. The party lasted until 5am. I had a train to catch at 9am. I crashed. The French stayed out for two more hours. The next day I took the train to London at 9 in the morning. The Eurostar train was high speed and whipped through the chunnel at breakneck speed, leaving us with our ears popped on both ends. London is gearing up for the Olympics, but I saw none of it, opting to catch a train to Oxford to see my good friend for lunch, before turning around and coming back to Hampton Court Palace where my family rented the Fish Court to have a reunion, 16 years later, of our first family vacation. It’s a full week of vacation for them, but I was only there for the night. Dinner was at a new Lebanese restaurant in the town, and dessert was a bottle of Graham’s port bottled 1912–its 100 year anniversary. It is hard to imagine how much different the world was when every person who made that bottle was alive and well and optimistic. It has been only 100 years, a blink in history, but an eternity for a young mortal trying to imagine how dead and buried he will be when 2112 rolls around. In the last century there were two world wars, three brutal totalitarianisms, the transformative liberalization of the global economy, the internet and the politics of interconnectivity, a cold war and a space age. It is hard to imagine what will happen in the next 100 years. The port was delicious and perfectly preserved.

The next day I took the train to London at 9 in the morning. The Eurostar train was high speed and whipped through the chunnel at breakneck speed, leaving us with our ears popped on both ends. London is gearing up for the Olympics, but I saw none of it, opting to catch a train to Oxford to see my good friend for lunch, before turning around and coming back to Hampton Court Palace where my family rented the Fish Court to have a reunion, 16 years later, of our first family vacation. It’s a full week of vacation for them, but I was only there for the night. Dinner was at a new Lebanese restaurant in the town, and dessert was a bottle of Graham’s port bottled 1912–its 100 year anniversary. It is hard to imagine how much different the world was when every person who made that bottle was alive and well and optimistic. It has been only 100 years, a blink in history, but an eternity for a young mortal trying to imagine how dead and buried he will be when 2112 rolls around. In the last century there were two world wars, three brutal totalitarianisms, the transformative liberalization of the global economy, the internet and the politics of interconnectivity, a cold war and a space age. It is hard to imagine what will happen in the next 100 years. The port was delicious and perfectly preserved.