HAVANA, SEPTEMBER 6, 2016 — “I’m not a big fan of Fidel,” our guide Jorge* says. We have known him for less than ten minutes. The driver, who speaks little English, nods approvingly. “His name is Fidel, too” says Jorge, patting the driver on the back. “This is the good Fidel.”

The first assumption I had about Cuba was shattered. I had assumed the people would be reticent to discuss their feelings about the regime, the party, or their leader. They were not. Almost all the Cubans we met were all too eager to relate their stories of living under the regime, in the past and in the present. Those that weren’t explicit spoke about Castro the way that a coworker might diplomatically criticize an underperforming boss. Our questions were often answered as if no other explanation were necessary: “Es Cuba.”

Es Cuba indeed. From the moment we landed in Havana the day before, direct from Panama City, it was immediately apparent we were not in Kansas anymore. The airport is an exemplar of Soviet-era architecture with brutalist concrete pylons, stretches of burnt orange tiles and adornments and long hallways with low ceilings and dim lighting. Where other airports might offer shop after shop of bookstores, coffee shops and restaurants, the Havana airport shops only have an abundance of certain items we will see many times: foreign candy imports, tobacco, tourist paraphernalia, and alcohol. Everything else is scarce, including food, water, soft drinks, snacks, magazines, books, toiletries, and medicine, none of which can be found. In the restroom, only half of the toilets have toilet seats, and there is a conspicuous lack of soap in the dispensers, no paper towels, and non-functioning hand dryers. To suddenly find ourselves in a place with plenty of cigarettes but no soap was a jarring experience, and it would not be our last.

“Fast Food” at the airport–so fast you can’t see it.

Upon arriving, our first task was to change our money. The local currency is two currencies. The convertible peso (CUC) functions as their hard currency—roughly 1:1 with the dollar—and is the only Cuban peso that trades for foreign currencies. Cuban pesos (CUP) are what the government spends, and are accepted at state-owned businesses, which until recently were all businesses. Not surprisingly, Cubans prefer to transact in CUC, and as we understand, they associate the two currencies with two different conceptions of quality. A “CUC place” will invariably deliver higher value, whereas a “peso place” is a euphemism for a shoddy, cheap, state-run service. It didn’t take us long to figure out that CUC was not only the currency of the tourist economy, but of the fledgling private economy as well, as some businesses who only cater to locals will still accept CUCs. As we will find out, more and more Cubans are breaking into this CUC economy and entering an emerging middle class with disposable income.

Upon leaving the airport the first thing to strike us was the cars. We felt immediately thrown back to a movie from classic Hollywood, complete with a lineup of 1950’s luxury automobile brands: Chevrolet, Oldsmobile, Buick, Cadillac, DeSoto, and Ford. And of course, there was an array of Soviet-era utility cars from Lada and the like. The few modern cars scattered about stuck out painfully. We also could see quite a few 1990’s-era European cars: Volkswagens, Peugeots, and so on. It was quite the hodgepodge.

Cuba’s car economy is unique in the world, a natural outcome of a state-run economy that only provides rationed cars to the political elite and some of those in select professions (like doctors), and has no legitimate market in automobiles. We find out later that the black market value of a new car is north of $260,000 and can be as high as $700,000 (that’s US dollars). The worst used car can be got for $7,000. It’s not surprising that Cubans value their cars above all else, which has translated to the plethora of 1950’s American cars on the roads, missing seatbelts, poor gas mileage and all. These are cars that have been preserved far beyond their natural lives and the age shows on most of them: from gutted interiors, non-functioning door handles, nubs where the window cranks used to be, rusted frames, cracked fenders, sputtering engines, creaking gears, torn and faded original leather seats, cracked paint, and every other car malady imaginable. Frequently we see a local car owner performing repairs, with the car jacked up, hood splayed open and parts strewn over the sidewalk. I would not be surprised if most Cubans are better mechanics than most mechanics anywhere else in the world.

A pretty typical scene in Old Havana. Lots of old cars everywhere you look.

Cars have also transformed into a new business opportunity in the last couple years, as Raúl Castro’s government has relaxed controls on transportation enterprises, in addition to restaurants and hotels. Many of the cars we see have been restored to their former glory, down to new paint jobs, new stereo systems, air conditioning and modern engines swapped in. We find out that a driver of these retrofitted old cars can make up to $50 per hour from tourists, not bad for a country whose average monthly salary is $23.

Retrofitted convertibles waiting for fares.

We spent our first day exploring our neighborhood, Vedado, which we will later find out is the most modern and one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Havana. It’s hard to believe it. Many houses on our street would be considered condemned by the standards of any major American city. Those that aren’t abandoned outright are in late stages of decay, held together by decades of do-it-yourself fixes we see Cubans performing constantly. It’s common to see lead paint peeling, door and window frames warping, and exposed concrete, rust and wiring. Many of these houses are former mansions stripped of their pre-revolution glory, overgrown with weeds, foundations literally crumbling before our eyes. It’s hard to believe there are people living in the crevices of these stone ruins, but we see them through windowless window frames. Some of these houses are completely gutted, down to the studs, or collapsed altogether.

Vedado was lively with activity: children coming home from school, parents and babies, cats and dogs wandering about, men pushing hand carts with construction supplies, women carrying bags from the fruit market down the street. We rented an Airbnb (recently allowed to operate in Cuba) whose owner has renovated half of her house for guests, which in turn is the top floor of a pre-revolution duplex. The bottom floor looks abandoned with its doorless entryways and unlit interior, but is occupied.

Grand old house in Vedado.

We walked to the Meliá Cohiba, a luxury hotel on the seaside Malecón esplanade, taking in its tacky oversized marble lobby (it actually reminded me a lot of the Trump Taj Mahal in Atlantic City). Meliá Cohiba is state-owned, along with the glorious old hotels and nightclubs of the past: Hotel Nacional, Hotel Parque Central, the Tropicana, the Floridita. These were hotels and clubs once owned and frequented by American millionaires and mobsters, the center of a thriving and prosperous economy which brought celebrities, artists, writers, wanderers, sunbathers and entrepreneurs to these sunny shores. When Castro took over in 1958, the state nationalized all of these tourist destinations. Today, they are shadows of their former glory, sharing many of the same misfortunes as the houses and mansions we saw.

One gets the sense that Havana has been lost in time, frozen in 1958 at the dawn of the most successful half-century in world history. The rest of the world has seen largely peace, prosperity, global trade, new technologies, the internet, cheap travel, a renaissance of architecture and music and literature, an explosion of democracy and expression, the shattering of international borders, economic stability and a new world order based in theory if not always in practice on human rights and dignity. Cuba just introduced heavily censored 56k dial-up internet, only available to the political elite and tourists, with some slow hotspots to the public available as of 2015. SMS still does not work for locals.**

Old Havana street; late afternoon.

In Europe and America, we speak of “prewar” and “postwar.” These wars are often the defining moments in our history across which so much changed they create two distinct periods with different moods, politics, economies, social orders, and realities. In Cuba, the moment that matters most is the moment when Castro, Che and their ragtag band of Marxist revolutionaries upended the Batista dictatorship and marched, guns blazing, into the presidential palace. From that moment on, every Cuban speaks of “pre-revolution” as if it were an era lost forever.

* * *

It is Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución we find ourselves with our new friend Jorge.

As any student of Communism will tell you, the Revolution never ends. It is critical to the policies of the regime that there is always a capitalist enemy to defeat. Legitimacy is achieved by representing the upending of a social and economic order where the elite control the means of production, to one where the people do through nationalization. Of course, once nationalized, the economy becomes taken over by a new elite whose methods of control are even more violent and regressive. That is why the Revolution must never end—because if a status quo of unilateral power becomes established, it invites a new revolution based on the same principles. This is why the Cuban constitution states, for example, that “artistic creativity is free as long as its content is not contrary to the Revolution.”

Old car repairs–a common sight on Havana streets.

That is also why, for 54 years until he handed the reigns of power to his brother, Fidel Castro lectured on the ongoing revolution and its benefits to crowds of millions in this very revolutionary square. It is a brutal place, the size of two football fields paved entirely in white concrete baking under the Caribbean sun. Portraits of Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos are displayed on government buildings surrounding the square, with an imposing memorial to Cuban national hero José Martí keeping watch from the center. Images of Fidel and Raúl Castro are not displayed, apparently because of a Cuban law that prevents public iconography of living revolutionaries (interestingly different from the norm in Mao’s China and Kim’s Korea).

Jorge is telling us about Fidel Castro’s 4- to 6-hour political rallies at this square, which would be broadcast on every television channel. “Everyone in Cuba watched it,” Jorge says, “Because we didn’t know how long the speeches would last, and the soap operas would come on afterwards.” We laughed. He continues. “We would keep the volume down so that Castro would become background noise. When he said ‘¡Patria o Muerte, Venceremos!’ [homeland or death, we will overcome], that’s when we turned up the volume. That’s when we knew the speech was almost over.”

A Lada taxi rumbles past an apartment building; central Havana.

Jorge is, like many Cubans we will meet, a multi-entrepreneur who has active businesses giving tours, selling cigars, teaching English and French, and helping Cubans with their immigration paperwork, all under the table of course. That’s the way the economy operates here. On our walk through Havana, we see street vendors selling tortillas, bananas, ice cream, makeshift barber shops and beauty salons in the empty shells of former houses, makeshift restaurants (paladars) and bars serving food and beer off of porches. In the last couple years, many of these businesses have been allowed to start operating legally; previously, they were all underground. Jorge explains to us that the official salaries offered by the government for services—such as driving garbage trucks—are laughably small, so almost everyone with an official job will have several jobs on the side. Those garbage truckers, for example, will siphon the valuable fuel left over from their routes and sell it on the black market, where customers will pay half of what they would pay for gas from the state-owned gas stations. And of course, Jorge is telling us this as we drive around in a car operated by Fidel, another entrepreneur whose beat-up 1955 Chevrolet Bel Air makes him far more money than he would make operating a state-owned, air conditioned, brand spanking new yellow taxi.

To give us a sense of just how low official salaries are, Jorge tells us that last year, the government raised the salary of doctors to $50 per month, after sending 4,500 doctors to Brazil to help with a medical crisis in 2014 and having many of them never return. It’s not surprising that even doctors in this economy look for any opportunity to make ends meet. Jorge’s doctor, we find out, sells Jorge his extra phone line for $60 per month so Jorge has access to 56k dialup internet (internet in private homes is currently illegal). Another doctor we hear about sells bootlegged movies from his bicycle to scrape together more cash. And they must, because they cannot afford to do otherwise. Monthly rations of rice and beans provided by the government amount to only one week’s worth of food. That means the other three weeks the people are forced to fend for themselves. It’s no surprise that enterprise has flourished underground, in the most unlikely places. Cuba might have more entrepreneurs per capita than anywhere else in the world.

Tourist market, by the wharf.

Jorge and Fidel took us around the city to point out more Havana peculiarities, including “Coney Island,” which despite its name is more of a small-ball kiddie park like you would find in an underwhelming tourist town. We saw the classic nightclubs of prohibition-era Havana, now all but abandoned, and the ex-Soviet, now Russian, embassy, which squats imposingly and palatially across several square blocks, epitomizing the concrete brutalist architecture of that era. And we drove past the estate of Fidel Castro, completely hidden behind overgrown brush, but bigger than anything we had seen so far.

We went for lunch at a CUC restaurant in Old Havana. The recently opened restaurant, Jorge explained, was funded by American capital, most likely through a family member as only Cubans can own property here. As a private business, this restaurant must provide better service and quality in order to stay afloat, something Jorge reminded us of after coming back from the bathroom. “This is the first year restaurants have had clean toilets in Cuba” he said matter of factly, and proudly. “They even have toilet paper.”

A brand new private ice cream shop in the old town. Delicious.

When a country is deprived of so much, so little becomes luxury. We are reminded of this constantly. Jorge needs to take one aspirin per day for a medical condition. He hasn’t had any in three months. It can’t be found (we gave him ours). We spent the meal getting a history lesson.

As Jorge explains it—and like everything else in this country, his view must be taken with a grain of salt—Batista was a petty dictator with a corruption streak who got caught in a Marxist fervor sweeping Latin America in the postwar period. He gave up with barely a fight, fled to Spain with $42 million in a suitcase and left the country to be taken over by Castro and his thugs. It became apparent very quickly that overthrowing one dictatorship does not mean another dictatorship won’t displace it, and Castro immediately went about practicing the normal Marxist playbook: seizing billions of dollars of private property, nationalizing all industries, and implementing the trifecta of communist control: stifling of dissent, rationing of all goods and services, and monopolizing of all labor. It didn’t take long for the best and brightest of Cuba to be driven underground and, if they were lucky, to flee to America, Mexico, and elsewhere, leaving behind an empty legacy of wealth: buildings and goods with no human capital behind them.

Typical street in Old Havana. Prime real estate, too.

As Jorge takes us for a walk through Old Havana, a mountain of salt wouldn’t hide what we can plainly see. Early 20th century condominium and apartment buildings in disrepair. Entire blocks of pre-revolution townhouses in ruins. Street after street of potholes, rusted fences, graffiti, peeled paint, uneven sidewalks ripped up by tree roots, crumbling concrete facades, abandoned shops, restaurants, movie theaters, boarded up doors, broken windows. What were once beautiful facades and lively pedestrian streets are caked in layers of filth and grime and dirt. The smells of exposed food, cigar smoke, sewage, rotting trash, and burning diesel all mix in a powerful cloud of odor wafting around every corner.

It could be a war zone. But it’s not—it’s merely the result of decades of neglect, imposed upon a country by a man whose face is plastered on every official poster and whose accomplices adorn t-shirts in every tourist shop. It’s the expected consequence of a state-owned economy that prevents Cubans from providing basic needs for each other.

Typical paladar in Old Havana.

I have many times been in a developing country. Never have I been in a de-developed country.

There is something uniquely sad about Cuba. Unlike other poor countries in the Caribbean, Cuba had everything, and it was turned into a trash heap of human and material misery. The people who did it have not been held responsible; in fact, they’re still in power. And the people who have suffered for decades have been robbed of their wealth, their human capital, and worst of all, their time. “You can’t get time back” Jorge sighs. “We lost 58 years. We went backwards in time. And the saddest thing for me,” he says, “is the potential we could have had.”

* * *

We met Daniel the next day, through a mutual friend. Daniel speaks no English but was happy to be our driver and guide for the day. We left at 7:30 in the morning and before long we were bumping down the pothole-ridden highway to Pinar Del Río, the western tobacco-growing region where many of Cuba’s legendary cigars are cultivated and rolled.

On the two hour trip, we had plenty of experience with the countryside. Hitchhikers were everywhere. It turns out that, unsurprisingly, any semblance of public transportation in the country is broken. In the cities, people can wait up to 3 hours for a bus, whereas in the country city-to-city transport is nonexistent. Since a car is a luxury most Cubans can’t afford, they’ve adapted their own ‘sharing economy’ where all cars offer ride shares for a price, as well as private busses which are essentially pickup trucks and vans whose drivers will sell rides.

Woman buying tortillas from a street vendor. Like much of the commerce in Cuba, makeshift and likely black market.

There’s only one main highway in Cuba (it’s a long and narrow country), and on this particular stretch of road, we encountered only one gas station/rest stop about halfway. Some prepared food was offered here—nothing we could eat—but they were out of many items. Long cabinets with a smattering of baked goods were mostly empty. Some foreign imports were available though—candy, chocolate and the like—so we were able to stock up on ‘food.’ We had started noticing a pattern where stores would have an abundance of some types of goods and a shortage of others. This shouldn’t be surprising for any student of economics.

In Cuba, in cases where the official price of a good is lower than market value—for example cars, public transportation and most food—scarcity and rationing are the norm and long lines form when no other options are available. We have seen lines for all kinds of goods including bread, medicine, and ice cream. One woman we met, Rosa, has to wait more than a year to see a doctor for her condition, and she still has no idea how serious it is.

Where’s the meter for the horse cart? A common sighting in Pinar del Río.

Where private enterprise is not allowed, a black market has emerged to offer higher prices but guaranteed availability across a suite of goods and services. The gas station we were at was state owned, so there was a shortage of most of the food on offer. Of course we didn’t know how to access the black market in this area, but one undoubtedly exists.

In those cases where the government price sits above market value—for example with taxi fares, hotel rates, tobacco and alcohol—other private enterprises and black markets have developed to deliver equal quality goods at a fraction of the cost. There will also be, as expected, an abundance of these goods in state run stores, as there was at the airport, and in this gas station. There was no problem here getting candy, chocolate, alcohol and tobacco, although right now we only wanted the first two.

We drove through Pinar del Río which seemed to be doing pretty well. Perhaps there were fewer pre-revolutionary buildings and materiel to notice relative decay. In any event, a communist government may end up supporting the people in the countryside better than those in the city. We saw a lot more revolutionary advertisements in the country, more statues of party leaders, more proclamations. We also saw more lines for food. So it’s hard to tell whether rural support for the regime is actually higher, or whether, perhaps, the country is favored by the regime because of the necessity for food only the country provides, and tobacco which is such a critical state-owned industry. In any event, it was important to see another side of Cuban life, where Castro and his allies may not be universally despised.

All gas stations are state owned. It’s rare to see people filling up; the car at the pump has government plates.

One thing we did see in the country that I haven’t seen since my time in post-Soviet Romania: horse-drawn carriages have replaced cars for much of rural Cubans’ industry and transit. That was astounding to me—whereas Havana has regressed to the 1950’s, the countryside has regressed to the dawn of the automobile.

At the first tobacco plantation we visited, we met Nardo. Like Jorge, Nardo taught himself English from American TV shows and music, supplemented by paying a private tutor. When I asked him if he learned any English in school, he shook his head and answered: “School is free here. You pay for nothing, you get nothing in return.” It was interesting to get Nardo’s perspective, as someone who interacts frequently with foreign tourists but also grew up in the countryside where access to foreign capital is limited. I asked him if he thought American tourists would be good for the country, and he said “It will be good, but it won’t change anything about the country.”

One of my assumptions about Cuba before coming here was that the people would blame America for their misfortune. As it turned out, quite the opposite was the case. Not only do the people love America and Americans, but signs of American fandom are everywhere. Flags adorning windshields and coffee shops. American flag t-shirts and tank tops. This is not just for our benefit. Many Cubans have relatives in the US and unsurprisingly there has always been a close unofficial relationship between the two countries. Americans send over $2 billion every year to Cuba, person to person, making America perhaps the largest subsidizer of the Cuban people, who depend on that money to survive. One worker at the plantation, when I admired his brand new leather shoes, smiled and said “de mi familia en Miami.”

One of the boys didn’t want to take a picture. In central Havana.

We learned that Cubans long ago realized that Castro’s long-standing scapegoating of the American embargo*** for the poverty in the country was a tactic to justify his own incompetence, much in the same vein as Hugo Chávez. It turns out that when a government says something is true over and over again, and the evidence in front of their eyes says otherwise, people tend to believe the evidence over the rhetoric. When Obama came to visit post-revolution Cuba—a first for American presidents—Cubans celebrated for weeks and lined the roads on his arrival route, waving American flags. It probably isn’t a thrill to the Cuban government that Fidel and Raúl Castro are half as popular as Obama amongst Cubans according to a 2015 poll, enough so that Fidel published a lengthy editorial slamming Obama after his visit.

Of course Cuba’s misery is the fault of Cuban government policies. Cuba has been cut off from American tourists and capital and products for the last 56 years, but it has had the ability to trade with almost every other country in the world. Of course there is no way that a well functioning economy with trade routes to the outside world would suffer because of one trade embargo with one country, when all goods Cubans could possibly want are available from many other countries as well. The evidence is all around—there are non-American brands for every major product here, from cars to candy to retail to alcohol to hotels. Cuba is not suffering because it doesn’t have access to US products and capital. Cuba is suffering because every import is controlled by the state and those controls lead to misappropriation, inefficiency, shortage and graft, when such imports are allowed in the first place.

America bling everywhere.

However, it is unsurprising to me, at least, that the relaxation of the American embargo is coinciding with the letting up of price controls and restrictions on free enterprise here. I suspect that Raúl Castro and company know that it’s only a matter of time before free markets emerge in Cuba, and the only way to retain legitimacy through the transition is to take charge of the change. If the embargo, the justification for misery, is lifted around the time when free enterprise and free flow of capital is allowed back into the country, Castro can continue to tell the biggest lie his government tells while guiding the country away from state-owned industry.

That’s all speculation of course. But when I asked Nardo about whether the lifting of restrictions on free enterprise in the last couple years has been good for the country, he said “Yes, for some people. And that’s good enough for the government.” From the countryside, it must be hard to see the all-too-slow dismantling of this failed and broken system from a distance. The government can’t let up too quickly, or it delegitimizes itself.

In the state-owned tobacco industry, planters like Nardo are allowed to sell 10% of their crop privately while the government buys 90% at a fixed price. The 10% goes for much more on the private market, where it is turned into cigars for consumption at even lower prices than the government charges for finished cigars. Where the massive spread goes between what the government pays for tobacco and what it sells cigars for, I wasn’t able to suss out, but I suspect it has something to do with the size of Fidel Castro’s mansion and the $260k new cars driving around the city with government plates.

Old Havana street.

Until a couple years ago, planters like Nando had to ‘sell’ 100% of their crop to the government, but the new rules have allowed for some limited maneuvering. That ultimately will be a good thing for the farm economy, and seems to have already made a difference. Jorge told us that until a couple years ago even common fruits like mangoes, papaya, and pineapple were not to be found on any market, for any price. He also told us there are some fruits he still hasn’t seen in more than 20 years.

We learned a lot about the condition of agriculture in Cuba. Before the revolution, Cuba was a world famous exporter of mangoes, sugar cane, coffee and tobacco, among other tropical fruits. When Castro took over—again, not surprising to students of communism—he mismanaged the farmland into the ground, literally. At one point, according to Jorge, he razed thousands of hectares of lush orchards to make room for cattle grazing. And yet, according to the Economist, “in a place that before 1959 boasted as many cattle as people, meat is such a scarce luxury that it is a crime to kill and eat a cow.” Years later, as we drive down the highway, we see miles and miles of barren land. Right now, Cuba imports over 70% of its agricultural consumption.

As a result of the revolution, the best planters and rollers moved abroad to other tropical countries like Dominican Republic and Nicaragua. This has resulted in other cigars catching up to Cubans on quality. Fortunately, unlike with coffee and mangoes, Cuba has retained its reputation for the best cigars in the world. But it isn’t hard to see how stifled the industry has become since coming under state control. For instance, despite there being a near infinite combination of cigar varietals that can be created by combining different species and fermentations of tobacco in different ways, only a handful of official state brands of cigars are permitted to be sold. So the creativity of the planters and rollers in coming up with new cigars is lost, for now, to the global market. But they certainly enjoy inventing new kinds of cigars for themselves.

Highway watermelon “store.” $1 per melon.

Daniel drove us back to Havana, on the way stopping for watermelons on the side of the road: $1 per melon. These makeshift enterprises are how most Cubans get by. He hid the watermelons below the floor of his trunk, with the spare tire. He wasn’t taking his chances with the checkpoints; on the way west, we had passed a random inspection, as officials are always looking for people smuggling food. Daniel wasn’t taking any chances that his watermelons would be confiscated or he would be fined or worse, imprisoned. He has two kids to feed.

If there was ever an example of the brutality of a Marxist regime, this was it. That one can’t even carry fruit without committing a crime—that the crime is betraying the revolution, not preventing people from feeding themselves—is too much to bear. Cuba has made its population criminal because they want things that improve and sustain life. It should not be a crime to want these things, but here it is a crime. “Crime is different here,” Jorge had told us. “We are all criminals in Cuba.”

* * *

When I told people I was going to Cuba, the reaction was predictable. I was told I was lucky to witness Cuba because it was “untouched.” I was told something along the lines of: “Oh, you get to see Cuba before Starbucks and McDonald’s go down and ruin it all.” I heard the same thing from some Americans I met at El Floridita. I confess part of me shared in this naive romanticism about Cuba, that somehow there is a ‘purity’ to Cuba that will soon be ‘corrupted.’ I was wrong about this. Not only because of my naiveté about the condition on the ground in Cuba, but because of the insidiousness such a belief implies about what the Cuban people want and deserve.

“Untouched” is a romantic way to look at the poverty that Cuba has become. There is nothing romantic about poverty. Poverty is sad. Poverty is sick children and malnourishment. Poverty is no books or school supplies. Poverty is no toilet paper, no soap, no toothpaste, no clean water, and unmet basic needs. Poverty is constant exposure to punishing heat and humidity. Poverty is torn up shoes and broken cars. Poverty is dangerous tools and equipment. Worst of all, poverty is wasted human capital: time spent waiting on lines for food instead of producing goods and services to better society. Poverty is unwritten literature, unsung music, unconducted experiments, undiscovered breakthroughs, and unfulfilled ambition.

Apartment building in decay; central Havana.

There is nothing pure about revolutionary Cuba. The Cuba of Fidel and Raúl Castro is a wasteland of broken people and broken dreams. For 58 years, Fidel Castro has bled the wealth of this country dry intentionally, prepared to let his people die rather than acknowledge the inadequacy of his broken political ideology. We know this firsthand now, since we have actually met people who lived through it. We met one Cuban who worked in a graveyard in the 1990s, the decade Cubans refer to as the “Special Period.” It was in the haze of post-Soviet collapse that Castro refused to allow foreign imports and, of course, with local production at miserable lows, it didn’t take long for people to start starving. Rather than betray the principles of the Revolution, Castro was preparing teams of body collectors to tour Havana and haul the dead back to the graveyard to be buried in mass graves. That is the legacy of making a country poor, and the wounds won’t be healed for decades after the regime is out of power.

Of course, the Revolution needs to keep people poor, because poor people can’t fight back. Poor people can’t afford to agitate. Poor people need to keep showing up to their jobs to collect their pitiful paychecks. Poor people need to keep waiting on line for their less-than-subsistence rations to keep from starving. If poor people aren’t allowed to fend for themselves, they must wallow forever. The only thing poor people can do, if they’re lucky, is escape. One woman, Donna, who sells local art, told me, “We love America. I wish we could go there.”

Car comparison: party member vs. regular citizen. The blue striped license indicates the car belongs to a party official or VIP. EDIT: apparently it’s state owned tourism vehicle, not a VIP. Blue just means state owned, but they can come in different varieties. In any event the blue plates are almost always on nicer cars than the white plates. Thanks, commenter.

Wealth is an anecdote. Wealth gives people power to fight back, to challenge the status quo, to create jobs and opportunities, to invest in food and clothing and productive capacities. Cuba needs wealth, and not wealth that goes to the apparatchiks and officials in their $260k cars and mansions. Wealth that actually goes to the people, in the form of jobs, industry, and investment.

The sadness is not that Starbucks is coming to Cuba. The sadness is that Starbucks has never come to Cuba.

The sadness is that no foreign brands have come to Cuba. No Austrian coffee shops, no Japanese dollar stores. We’re finding some limited foreign retail brands, apparently only recently allowed in. But even Coca Cola is hard to come by. These foreign franchises represent jobs, investment, and opportunity for the Cuban people. The Cuban people have been cut off from the world, from not only the cheap high quality goods and services that improve quality of life, but the freedom and the disposable income to improve their own lives and pursue their own happiness.

All-but-abandoned complex in old town Havana.

Starbucks and McDonald’s will not ruin Cuba. Cuba is already ruined. As American tourists, what we wanted—-desperately wanted—is some way we could help the people rebuild. The answer is not lifting the US embargo, although extra American tourist dollars would be good. But if those dollars go immediately to waste, it won’t change the country fundamentally. We heard many times from many people that the system is the problem. They need more liberalization, more private enterprise, more allowance of foreign imports. And that can only happen if Cuban communism goes the way of Chinese and Vietnamese communism: embracing free markets, allowing foreign investment and free capital flows, and letting the people get to work for themselves.

Waiting on line for bread. Central Havana.

And according to Jorge, whose reading on the subject is far better than mine, this won’t happen until the ‘old guard’ of the revolution—Fidel, Raúl and other party leaders, all over 80 years old—are no longer in power. He tells us with a guilty whisper: “We must wait for the biological solution.”

That night, we walked the ramparts of Havana, on the ocean, where just 80 miles over the horizon is Key West, Florida. We mingled with hundreds of local young people who spend their nights looking out into the blackness that in any other country would be thriving with lights from incoming and outgoing ships representing the entirety of the world’s commerce and nations.

* * *

As we toured the old town of Havana, we took in all we could. We shopped at an official tourist market right off the wharf where the cruise ships come in. We discovered gems of old Havana: the church of San Francisco, the old Partagás cigar factory, the capitol building. We had daiquiris with the bronze statue of Ernest Hemingway at the Floridita. We saw one of the oldest cathedrals in the hemisphere.

As we explored the city of Havana, we discovered that the bleakness of Cuba’s past is fast giving way to a prosperous future.

Recently, the regime started allowing private enterprises to operate here on a limited bases. They started with cars, hotels, and restaurants, but opened up over 200 occupations. Now Cubans can become barbers and salon professionals, bus drivers, floor polishers, electricians, and computer programmers as well, all without having to hand over 100% of their work product in exchange for a measly ‘salary.’ Many Cubans can now work for themselves, to the tune of over 20% of the workforce now in the private sector.

Art market on the bay.

Signs of a Cuban renaissance are everywhere. As recently as two years ago, according to friends of mine that visited, there were no restaurants or bars outside of the tightly controlled state-owned hotels. Now, restaurants, hotels, bars, and shops are popping up all over the place, offering better service and sometimes, better prices. We ate at some fantastic new restaurants and were able to patronize private ice cream shops, our private Airbnb, and of course private cars. We visited a new boutique hotel opening soon, completely renovated (although they imported everything, from the tiles to the tables to the business cards, from Italy). People fixing and renovating storefronts and houses, limited advertising on the sides of buildings, a plethora of new businesses servicing tourists in the old town. Music pouring out of every restaurant beckoning people in. We see a fortune teller who charges $200 per reading, 10 times the average Cuban monthly salary, to tourists. She’s probably one of the richest people in the country. This is all new to post-1958 Cuba.

As Nardo told us, these changes are only helping some people for the time being, which makes sense. Only those with money to spend can afford to invest in, and buy products from, non-state owned business. But these businesses create more people with money, and this money forces its way not only into the industries opening up, but the myriad of industries which depend on them. For instance, allowing a private restaurant to operate freely must mean allowing the vendors who provide the restaurant with food, tables and chairs, ovens, deep fryers, kitchen utensils, and uniforms to operate freely as well. Allowing a private barbershop must mean allowing private scissor sellers and shaving cream manufacturers. Not allowing these dependent industries and imports to develop would mean asking businesses, like the people, to circumvent tight controls to acquire the goods and services they need on the black market, which they will do, but at great cost to society.

We were fortunate to be at the home of a local for some drinks when our host took delivery of that week’s paquete, something I had read about and was excited to try firsthand. The paquete is a hard drive smuggled in from the outside world with weekly updates from all major Mexican and US TV shows and soap operas, music, news, sports, software updates and patches, and even iPhone & Android apps. Locals pay $1 to get paquete delivered for a couple hours where they have a chance to download whatever they want. It’s basically a black market for culture and entertainment, and allows Cubans to know everything about the US election, watch Game of Thrones and Netflix shows, stay updated on baseball, and pirate music. We also frequently see Cubans connecting to the internet near state owned hotels where there are slow, but working hotspots, though they have to buy from the state’s internet monopoly and it is heavily censored. Some Cubans we met are even on Facebook. They are able to keep in touch with relatives abroad, which means they are in touch with the outside world.

The only internet available to most Cubans is around hotspots like these next to state-owned hotels. Only 30% of Cubans have some access to the internet, although having internet in a private home is illegal.

So, with economy and society, it’s clear that the floodgates are being forced open. As new businesses flourish, they are creating jobs and a new influx of capital, which will be spent in turn on more goods and services. As Cubans get connected to the outside world more and more, they are able to access cultural capital abroad, as well as foreign markets and international trade partners. This will create new business opportunities. Cuba is starting to emerge again.

That night, we dined at La Catedral, a new restaurant in Vedado, where we were the only foreigners. Two young musicians, whom I had a chance to talk to about their budding musical careers, played jazz standards on piano and violin they had taught themselves. The mood was upbeat and one could easily think we were in a Argentinian bistro. The place was packed with local Cubans, enjoying a night out, probably aware that they are at the forefront of a new revolution in Cuba. For a moment it seemed that it was only a matter of time before the rest of the country can rejoin the world.

* * *

The only museum we visited was the Museo de la Revolutión. There, we were spoon-fed details of the brutality of the Batista regime and the noble heroes who overthrew it. We met the young, handsome revolutionary leaders who, full of optimism and certainty about their ideology, sought to bring the world forward by creating a Marxist utopia. We learned about the evil of the US embargo and how it has brought untold suffering on the Cuban people. We learned that the Revolution will last forever.

One can’t help but think about Orwell when confronted with such stone faced hypocrisy and deceit. His vision of the dystopian world of 1984 is eerily prescient here; a place where war is constant, where truth is fiction and history is erased. Where Fidel, the man himself, is incapacitated, and yet is still invoked as the moral authority of the nation and its prime political and ideological figurehead.

History crushes you here. We are walking amongst the carcass of Marxism-Leninism, 26 years after most of the world has abandoned this folly. Only in Venezuela, Cuba, North Korea, Zimbabwe, Myanmar, and a few other holdouts do people have to suffer this way any more.

Busy old town sidewalk.

You get the sense that politics, society, economy and history are all intertwined and the forces that have shaped this country and others like it are human and inhuman at the same time—human because they come from a profound sense of responsibility and desire to do good, inhuman because they result in so much evil and destruction of human lives and potential.

As we wandered the streets of Havana, our helplessness was overwhelming, not only out of our desire to want to better the condition of the people around us, but out of our shared experience, if even briefly, with what Cubans go through every day in even worse circumstances. There is a conspicuous lack of basic services found in abundance elsewhere. Grocery stores are a rarity; we only found two and they lacked fresh produce, household items, and any non-prepared foods. There are no bodegas or quick marts or soda fountains. Pharmacies are few and far between with little supply, only available rationed to those with permission. Even if I wanted, I don’t know where I would find toothpaste or toilet paper. The ability to pay a fair a cheap price for something I want, like a bottle of water or an apple, isn’t widely available, even to people with money. It is surreal to be in a place where dollars didn’t demand immediate service. Even in the poorest countries I’ve been to, markets are allowed to exist that provide these services.

Abandoned bar, maybe soon to be revitalized? Prime real estate in old town Havana.

All the while we were keenly aware of the luxuries that only we as tourists could afford. Air conditioned rooms to escape the punishing heat and humidity. Limited and slow access to wifi on occasion. Access to the international cell phone network–a real connection with the outside world even at $2.99/minute. If we are the most privileged in the country with foreign capital and currency, what hardships must normal Cubans endure?

If there were ever a doubt about the morality of markets over their criminalization, Cuba would be it. Markets are moral because they provide services and solve problems. They derive their morality from the fair exchange in value created, from the voluntary nature of every transaction. Certainly if markets were evil, as the revolutionary laws would have you believe, people would not risk life and limb to engage in them. There wouldn’t be a broad spirit of cooperation and subversion from the people to circumvent the laws to get what they need. People wouldn’t risk their lives sailing makeshift rafts to Florida or lining up at border crossings across South America.

Makeshift parking lot for jitneys in the old town.

Where is the morality of taking food away from people at highway checkpoints, of banning foreign investment and imports, in forcing people to work for meager wages and insufficient rations? Where is the morality of making medicine impossible to find, food impossible to procure, cars impossible to afford? What insanity allows such a system to stay alive for so long, and what must the Cuban people suffer before it is undone?

We spent our final night with Jorge in his flat. He and his wife are the face of the new Cuba. Born in the 50’s, their whole lives have been spent in the shadow of the revolution, but now they are bursting at the seams. As Cuba opens up and relaxes its policies, entrepreneurs like Jorge will lead the charge, providing tourists and locals services that will create wealth for him and his family, as well as well paying jobs and wealth for others.

Dinner was a panoply of local Cuban specialties, which have been scraped together from various sources: carrots and rice from rations, mangoes and pineapples from the local market (remember: these fruits are newly available in the last couple years), and homemade pancakes made from shaved root vegetables and spices. And we had fish, a real luxury, which we were appreciative they provided for us.

Over rum and cigars, we discussed politics, history, and of course, Cuba, with Jorge. He is well read by any standard. His bookshelf has hundreds of books, a full examination of political economy across Europe, Asia, and of course the Americas, with a focus on the history of war and totalitarianism of all stripes, including religious fundamentalism. He has the Black Book of Communism, books on North Korea, and many other banned works—all smuggled in by friends and entrepreneurs catering to a population hungry to read everything they can.

Jorge is, of course, everything that is contrary to the principles of Cuban revolutionaries, which is what made him such a fast friend: educated, self-employed, entrepreneurial, well read in liberal ideas, aware of what’s happening in the world despite the censorship, one of the few Cubans with internet in his own home thanks to a back alley deal with his doctor. I couldn’t help but thinking that our entire conversation, if recorded or reported on, would land him in prison immediately. He had no problem openly discussing Fidel, explaining to us that the real risk is taking a public stance. Protesting, which happens occasionally, is treated harshly, and results in no change.

The one grocery store we found. It was impressive to see so much food in one place.

We spoke freely and openly about the injustices that have been brought upon his people, soaking in the lessons to be learned from history about the futility of the very ideology considered sacrosanct by the leaders of his country. “To think that we have all suffered for 50 years,” Jorge said, “All because of a man in a funny hat and a funny beard, thinking he knows the answer to everything.” And he’s right.

This family is, or will soon become, part of the nouveau riche of Havana, thanks to the enterprising Jorge and his ambition. But even with money to spend, they struggle to get the things they need, which means wealth that wants to find new owners is struggling to break through. The toilet seat, we found out, was just purchased, after weeks of searching for one. Our “napkins” came from a Russian-branded packet of tissues. Our wine was a cheap bottled sangria from the state market. We couldn’t help compare this last meal with our first dinner, at a restaurant owned by a “friend of the party” whose family still lives in the 8-bedroom, 5-bathroom house on the property. After that dinner, we took a tour of the 1930’s mansion, and were proudly shown their Baccarat crystal chandelier. Comparing the party member who has built nothing with a $5,000 chandelier to the productive, hard working family with no real napkins is enough to make your blood boil. These are the fires that real revolutions are made of. The Cubans have it, and they practice their subversion quietly, but one day the full force of Cuban potential will be unleashed on the country, and the world.

Prime real estate, right next to the capitol building.

Take a mint condition 1950’s Cadillac. Drive it off the lot. Drive it to and from work for 50 years. Getting a new car isn’t an option. When it breaks, the owner must repair it out of pocket with improvised parts. New parts aren’t allowed. As the car gets louder, rustier, dirtier, and less reliable, depend on the charity of your friends to help repair it to keep it going. Eventually every part of the engine has been replaced. Limping along on hacked together fixes and the help of others, the car breaks down slowly over time, but thanks to the quality of manufacture, long shelf life of its fundamentals, and care of the driver, the car still putters along, though it can’t last forever.

So it is with a country. A country that represented the best if its time, the envy of the Caribbean, a jewel of prosperity and productivity and culture and music and history. This is the country that continues to limp along, engine sputtering, but with a strong engine and a good driver—it just needs to be let free. Let the Cuban people onto the open road, and it will be a marvel to witness.

* * *

Now that I am safely on American soil, after spending the week swimming in Orwell, I’m only now starting to think about what Americans can learn from Cuba.

Aside from the obvious, as in: don’t run a country based on the misguided theories of a 19th century Hegelian with no real world experience in economics. I can’t imagine that even the die-hard Bernie Sanders supporters want a state run economy; they just want to see a democratic socialism like in Europe, where economic perversions are democratically imposed and thus carry more legitimacy. Fine. Our mountain of unnecessary regulations and price fixing and tariffs aside, America isn’t going the way of Cuba any time soon.

One lesson that Cubans can teach us is something they understand intuitively; that the line between a job and a business is blurred to nonexistent; the skills are offered for cash each way and the important distinction is whether one is free to trade labor for a price acceptable to both sides, or forced to work for less than subsistence wages because the government is the only employer. When we were told, proudly, that “a private business means that a person works for themselves, and the government can’t make them go down to the revolutionary square to cheer on the party,” that’s what we’re being told—that working for oneself is sacrosanct. It not only is a bulwark against poverty, it’s a bulwark against totalitarianism as well. The best weapon against tyranny is wealth. Not Bill Gates wealth, but “being able to feed one’s own family” wealth—a country where owning one’s own destiny is the norm gives sovereignty to the people, not the government.

The next generation. A boy helps his father repair their Oldsmobile.

The other important lesson from Cuba is the importance of allowing entrepreneurs to operate, because entrepreneurs provide goods and services that people want, and even those that people need. We shouldn’t cherry pick how we define an entrepreneur—an entrepreneur can be anybody, working alone or working together with others, who solves problems for people. We glorify entrepreneurship in the US as an avenue for creating jobs, but jobs are secondary. The real benefit of entrepreneurship is the availability of more and better goods and services for a better price. An entrepreneur can have a business employing only one person—the entrepreneur—and still make a difference.

The best and captive market in the world for entrepreneurs is that market where the most basic needs are not being met, which means Cuba has become, and will continue to be, a haven for entrepreneurship in the years to come. How can we as Americans support this? I have been researching a lot into questions about owning property, importing basic things like aspirin and t-shirts, allowing for easier communication to and from Cuba, helping with language education—these are all things that people need. As America opens up to Cuba, we’re in a privileged geographical position, not to mention a cultural one, to help invest in this country.

* * *

* I changed most names and some details to protect people

** I’m still trying to verify this as it relates to Cuba-to-Cuba SMS. Was told by two people separately that it isn’t possible, but there’s nothing about it online.

*** Incidentally, if there were ever an example of the futility of embargoes and trade sanctions in order to change a regime, the Cuba embargo would be it. It clearly did nothing to change Fidel’s grip on power, and may have even extended it, by giving Fidel an excuse to continue impoverishing his people

I was in Denver for the 2008 convention where, though not able to score an invite to the floor, I was able to witness an America divided by the hot button issues of the day, some of which are still with us: same-sex marriage, abortion, the war in Iraq, and immigration. I watched the DNC convention speeches with anticipation and excitement for the next eight years, fully swept up in the anti-Bush furor and pro-Obama fervor of the time.

I was in Denver for the 2008 convention where, though not able to score an invite to the floor, I was able to witness an America divided by the hot button issues of the day, some of which are still with us: same-sex marriage, abortion, the war in Iraq, and immigration. I watched the DNC convention speeches with anticipation and excitement for the next eight years, fully swept up in the anti-Bush furor and pro-Obama fervor of the time. But I won’t deny I spent many hours obsessively checking FiveThirtyEight and Politico for minute movements in the polls. I secretly hoped Hillary Clinton would be our next president. Not because of any love for Hillary Clinton, but because of my love of the Republic and the long-standing political norms which are now

But I won’t deny I spent many hours obsessively checking FiveThirtyEight and Politico for minute movements in the polls. I secretly hoped Hillary Clinton would be our next president. Not because of any love for Hillary Clinton, but because of my love of the Republic and the long-standing political norms which are now  “Fast Food” at the airport–so fast you can’t see it.

“Fast Food” at the airport–so fast you can’t see it.

A pretty typical scene in Old Havana. Lots of old cars everywhere you look.

A pretty typical scene in Old Havana. Lots of old cars everywhere you look.

Retrofitted convertibles waiting for fares.

Retrofitted convertibles waiting for fares.

Grand old house in Vedado.

Grand old house in Vedado.

Old Havana street; late afternoon.

Old Havana street; late afternoon.

Old car repairs–a common sight on Havana streets.

Old car repairs–a common sight on Havana streets.

A Lada taxi rumbles past an apartment building; central Havana.

A Lada taxi rumbles past an apartment building; central Havana.

Tourist market, by the wharf.

Tourist market, by the wharf.

A brand new private ice cream shop in the old town. Delicious.

A brand new private ice cream shop in the old town. Delicious.

Typical street in Old Havana. Prime real estate, too.

Typical street in Old Havana. Prime real estate, too.

Typical paladar in Old Havana.

Typical paladar in Old Havana.

Woman buying tortillas from a street vendor. Like much of the commerce in Cuba, makeshift and likely black market.

Woman buying tortillas from a street vendor. Like much of the commerce in Cuba, makeshift and likely black market.

Where’s the meter for the horse cart? A common sighting in Pinar del Río.

Where’s the meter for the horse cart? A common sighting in Pinar del Río.

All gas stations are state owned. It’s rare to see people filling up; the car at the pump has government plates.

All gas stations are state owned. It’s rare to see people filling up; the car at the pump has government plates.

One of the boys didn’t want to take a picture. In central Havana.

One of the boys didn’t want to take a picture. In central Havana.

America bling everywhere.

America bling everywhere.

Old Havana street.

Old Havana street.

Highway watermelon “store.” $1 per melon.

Highway watermelon “store.” $1 per melon.

Apartment building in decay; central Havana.

Apartment building in decay; central Havana.

Car comparison: party member vs. regular citizen. The blue striped license indicates the car belongs to a party official or VIP. EDIT: apparently it’s state owned tourism vehicle, not a VIP. Blue just means state owned, but they can come in different varieties. In any event the blue plates are almost always on nicer cars than the white plates. Thanks, commenter.

Car comparison: party member vs. regular citizen. The blue striped license indicates the car belongs to a party official or VIP. EDIT: apparently it’s state owned tourism vehicle, not a VIP. Blue just means state owned, but they can come in different varieties. In any event the blue plates are almost always on nicer cars than the white plates. Thanks, commenter.

All-but-abandoned complex in old town Havana.

All-but-abandoned complex in old town Havana.

Waiting on line for bread. Central Havana.

Waiting on line for bread. Central Havana.

Art market on the bay.

Art market on the bay.

The only internet available to most Cubans is around hotspots like these next to state-owned hotels. Only 30% of Cubans have some access to the internet, although having internet in a private home is illegal.

The only internet available to most Cubans is around hotspots like these next to state-owned hotels. Only 30% of Cubans have some access to the internet, although having internet in a private home is illegal.

Busy old town sidewalk.

Busy old town sidewalk.

Abandoned bar, maybe soon to be revitalized? Prime real estate in old town Havana.

Abandoned bar, maybe soon to be revitalized? Prime real estate in old town Havana.

Makeshift parking lot for jitneys in the old town.

Makeshift parking lot for jitneys in the old town.

The one grocery store we found. It was impressive to see so much food in one place.

The one grocery store we found. It was impressive to see so much food in one place.

Prime real estate, right next to the capitol building.

Prime real estate, right next to the capitol building.

The next generation. A boy helps his father repair their Oldsmobile.

The next generation. A boy helps his father repair their Oldsmobile.

That was in 2005. It would still be three more years before Connecticut became only the third state to enact same-sex marriage legislation. Other states followed suit, but not without problems. In 2008, California’s infamous Prop 8 banned same-sex marriage in my current home state, rolling back a right that had been granted to gay couples previously, and prompting a litany of suits that have now reached the Supreme Court. But even in 2005, although it was still an uphill battle for millions of gay couples in the United States, it wasn’t unthinkable that the nation was at a tipping point. In just seven years’ time, a blink of the eye in legislative terms, nine states now allow same-sex couples to marry, with the first to allow it by popular vote in the last election. The president of the United States, for the first time, publicly acknowledged his support of the issue. Multiple Republicans and GOP insiders have acknowledged that there is little they can do about the eventual legalization of same sex marriage nationally. And in a stunning symbolic blow to the sadomasochistic social conservative movement, conservative-turned-libertarian Glen Beck is

That was in 2005. It would still be three more years before Connecticut became only the third state to enact same-sex marriage legislation. Other states followed suit, but not without problems. In 2008, California’s infamous Prop 8 banned same-sex marriage in my current home state, rolling back a right that had been granted to gay couples previously, and prompting a litany of suits that have now reached the Supreme Court. But even in 2005, although it was still an uphill battle for millions of gay couples in the United States, it wasn’t unthinkable that the nation was at a tipping point. In just seven years’ time, a blink of the eye in legislative terms, nine states now allow same-sex couples to marry, with the first to allow it by popular vote in the last election. The president of the United States, for the first time, publicly acknowledged his support of the issue. Multiple Republicans and GOP insiders have acknowledged that there is little they can do about the eventual legalization of same sex marriage nationally. And in a stunning symbolic blow to the sadomasochistic social conservative movement, conservative-turned-libertarian Glen Beck is  I could say a lot about this, particularly about South Africa which went from apartheid’s strict regulations on sex and marriage to full-blown marriage equality within 20 years, but it is amazing how steadfastly civil liberties can be protected as long as people keep speaking out for them. For there are plenty of people who would like this “sin” to be punishable by death. There are plenty of people who would like to see gays “cured” by the state, or see religion in general imposed upon children in classrooms. And, don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of our friends on the left who would like to tell people what foods they can eat, or what lightbulbs they can use, or what is appropriate to say and in which fora. There will always be people who believe they have a right not to be offended by someone else’s personal choices and beliefs, and they will work to take away our rights in turn.

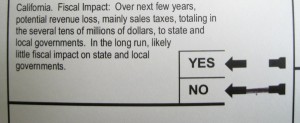

I could say a lot about this, particularly about South Africa which went from apartheid’s strict regulations on sex and marriage to full-blown marriage equality within 20 years, but it is amazing how steadfastly civil liberties can be protected as long as people keep speaking out for them. For there are plenty of people who would like this “sin” to be punishable by death. There are plenty of people who would like to see gays “cured” by the state, or see religion in general imposed upon children in classrooms. And, don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of our friends on the left who would like to tell people what foods they can eat, or what lightbulbs they can use, or what is appropriate to say and in which fora. There will always be people who believe they have a right not to be offended by someone else’s personal choices and beliefs, and they will work to take away our rights in turn. However, in practice, this seems like an exercise in futility. For one thing, the guides themselves are dense manuals that number at more than 150 pages each; a chore to read cover-to-cover for any person. Each ballot proposition (there are eleven of them) is painstakingly deconstructed and explained, no doubt by committee, and the “For” and “Against” arguments are provided by representatives from each side–these representatives are also, no doubt, chosen by committee. The result is a sanitized, extremely confusing, mishmash of populism, legalize, and financial voodoo that seems to make both sides of each proposition look like the other side is an Orwellian nightmare and the alternative is the only solution to California budget Nirvana.

However, in practice, this seems like an exercise in futility. For one thing, the guides themselves are dense manuals that number at more than 150 pages each; a chore to read cover-to-cover for any person. Each ballot proposition (there are eleven of them) is painstakingly deconstructed and explained, no doubt by committee, and the “For” and “Against” arguments are provided by representatives from each side–these representatives are also, no doubt, chosen by committee. The result is a sanitized, extremely confusing, mishmash of populism, legalize, and financial voodoo that seems to make both sides of each proposition look like the other side is an Orwellian nightmare and the alternative is the only solution to California budget Nirvana. Finally, some of these measures are straight wrong, or just illegal. City Proposition G reads as follows: “In Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the free speech provision of the First Amendment protects corporations as well as human beings…Proposition G would make it City policy that corporations should not have the same constitutional rights as human beings and should be subject to political spending limits.” Put simply, a city ordinance cannot take away federal constitutional rights. If Biloxi, Mississippi were to pass an ordinance that said “In Roe v. Wade, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that women have a constitutional right to an abortion…Proposition A would make it City policy that women not have a constitutional right to an abortion,” people would be up in arms, and rightfully so. The City of San Francisco doesn’t decide what is constitutional, especially after it has already been ruled constitutional. Even the

Finally, some of these measures are straight wrong, or just illegal. City Proposition G reads as follows: “In Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the free speech provision of the First Amendment protects corporations as well as human beings…Proposition G would make it City policy that corporations should not have the same constitutional rights as human beings and should be subject to political spending limits.” Put simply, a city ordinance cannot take away federal constitutional rights. If Biloxi, Mississippi were to pass an ordinance that said “In Roe v. Wade, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that women have a constitutional right to an abortion…Proposition A would make it City policy that women not have a constitutional right to an abortion,” people would be up in arms, and rightfully so. The City of San Francisco doesn’t decide what is constitutional, especially after it has already been ruled constitutional. Even the  First off, I am able to begrudgingly come to common ground with Mr. Krugman on some points: One, that the Euro is responsible for Greece’s woes. Mr. Krugman, like

First off, I am able to begrudgingly come to common ground with Mr. Krugman on some points: One, that the Euro is responsible for Greece’s woes. Mr. Krugman, like  The greater problem in this controversy is the continued hatred of immigration in general from the xenophobic right, and the weak economic opposition put forward by the protectionist left. As with so many things in our politics, the right and the left often find themselves strange bedfellows when it comes to questions of innovation and growth.

The greater problem in this controversy is the continued hatred of immigration in general from the xenophobic right, and the weak economic opposition put forward by the protectionist left. As with so many things in our politics, the right and the left often find themselves strange bedfellows when it comes to questions of innovation and growth.